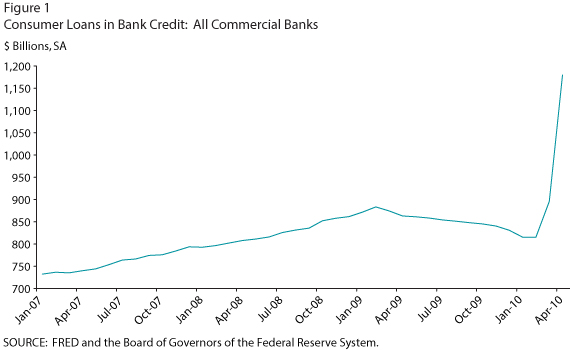

A Jump in Consumer Loans?

At first glance, the upward spike in consumer loans during the months of March and April 2010 (see Figure 1) seems to suggest a dramatic expansion in credit. The spike itself could be seen as a strong signal that banks have loosened credit standards or have originated more consumer loans in the wake of an improving economy. While there have been improvements in consumer loans recently, the dramatic increases over the past few months have been caused by a new reporting requirement issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board. Financial Accounting Statements (FAS) 166 and 167 have implications for how banks treat off-balance-sheet special purpose vehicles (SPVs). Moreover, these statements have more impact in certain loan categories and on certain bank types in particular.

During the run up to the Great Recession, banks regularly used an "originate to distribute" business model to remove assets from their balance sheets. Banks bundled up risky assets such as mortgages, credit cards, and auto loans into securitizations and sold them to investors in the secondary market. From a bank's perspective, selling off these assets in the secondary securitization market enabled them to take advantage of servicing activities and other loan sale income (fees and income associated with collecting and distributing loan payments and other services like tax payments) while passing along credit risk to a larger pool of investors.

Since the onset of the Great Recession, however, regulators and accounting rulemakers have analyzed the possible use of SPVs in distorting balance sheets and affecting bank safety and soundness.1 Seeking to remedy this, the Financial Accounting Standards Board instituted FAS 166 and 167 to establish a new set of reporting rules for how U.S. banks must deal with their off-balance-sheet SPVs. FAS 166 and 167 brought nearly $362 billion in assets and liabilities back onto bank balance sheets, a large percentage of which (roughly $322 billion) were consumer loans.

However, all banks have not been affected equally. The effect on the U.S. banking system is largely dependent upon the size of the bank. Larger banks took advantage of secondary markets as destinations for their securitized products, but smaller banks, especially community and regional banks, did not engage actively in securitization. Thus, FAS 166 and 167 have had a greater impact on the balance sheets of large banks. For instance, for commercial banks with more than $50 billion in total assets, consumer loan portfolios grew 42 percent from the fourth quarter of 2009 to the first quarter of 2010. Figure 2 illustrates the varying impact on the consumer loan portfolios of different sizes of banks.

A broader issue for the banking sector is how the consolidation of these assets on bank balance sheets will affect bank capital. The purpose of off-balance-sheet SPVs was to give banks smaller balance sheets and to remove assets, which allowed them to hold less capital to defend against the risk of losses. Thus, these banking institutions may need to increase risk-based capital levels in upcoming years to accommodate this increase in assets.2 Results from regulatory filings for the first quarter of 2010 suggest that banks have not started to increase capital yet, as they have been given roughly one year to complete this process. Based on recent bank profitability, banks should be able to use capital markets to increase private capital more than they were able to two years ago.

While this spike in consumer loan data is a result of past activities, consumer loans appear to be leveling off. The series in Figure 3 illustrates the consumer loan trend after adjusting for the accounting changes. Although the increase apparent in the unadjusted series has disappeared, the declines in lending do appear to be tapering off.

Notes

1 While some pre-crisis securitizations were characterized by subpar credit quality, credit quality has largely improved in the past year.

2 Please refer to the FDIC's Summary on FAS 166/167 risk based capital implementation: www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2010/fil10003a.pdf.

© 2010, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed